In the 1950s, a group of largely University of Washington (UW) professors, led by Lloyd S. Woodburne (1906-1992) – dean of the College of Arts and Sciences, began making wine at home. There would ultimately be 10 people who would go on to form Associated Vintners (AV), one of Washington’s founding wineries.

In the 1950s, a group of largely University of Washington (UW) professors, led by Lloyd S. Woodburne (1906-1992) – dean of the College of Arts and Sciences, began making wine at home. There would ultimately be 10 people who would go on to form Associated Vintners (AV), one of Washington’s founding wineries.

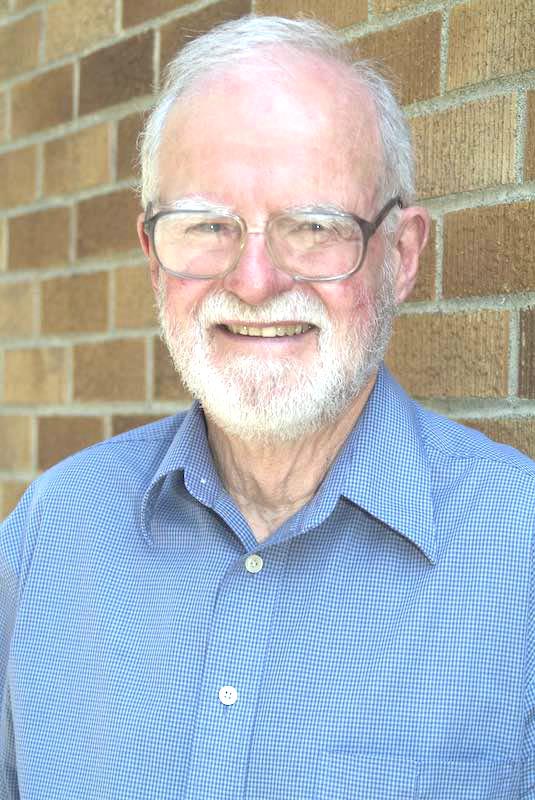

One of those men was Charles Sleicher. At the time, Sleicher was a professor of chemical engineering at the UW. Later, he became chair of chemical engineering and then professor emeritus. Now age 98, Sleicher is the last living member of the 10 original founders of Associated Vintners. (Founder Allan Taylor was the most recent to pass away, in 2021.)

“For much of my life I’ve been interested in wine,” Sleicher says. “Anything I could do to help and learn more about wine I tried to do.”

Sleicher now lives at Mirabella Seattle, a retirement community in South Lake Union. Like the rest of the AV group, Sleicher started out as a home winemaker.

“When I first started I went down to the railroad side-yard and bought Zinfandel grapes from a box car,” he says. The grapes came from California. “We had a big Italian community here. They went down and bought grapes from the railroad siding.”

The beginnings of Associated Vintners

Sleicher was asked by Woodburne to join his nascent group. “We were all amateur winemakers. We made wine at home,” recalls Sleicher. “We each chipped in a certain amount of money [to be involved].”

In 1962, the group incorporated and bought five and a half acres of land on Harrison Hill in Yakima Valley from William Bridgman. This would become one of Washington’s oldest and most revered vineyard sites. Today all of the fruit from this vineyard, including some of those original vines, goes into the DeLille Cellars Harrison Hill wine.

“It was a perfect place,” Sleicher says of the vineyard. He says “considerable research” went into selecting the proper site – no surprise for a group of academics.

In 1963, AV planted Cabernet Sauvignon, Chardonnay, Gewürztraminer, Grenache, Sémillon, and Riesling using cuttings from California. Other varieties were added from cuttings from a nearby vineyard.

They had difficulties establishing the site. “We had a bad frost that delayed everything by a year,” Sleicher says. Over time, some varieties did well; some did not.

“We gave up on the Grenache,” Sleicher says.

Early wines see immediate success

In 1967, AV made its first commercial wine in a warehouse in Kirkland, which Sleicher describes as a “cinderblock building.”

“That was kind of a makeshift winery,” he says. “We’d have grapes shipped over overnight so they were still cool in the morning. We’d get there at dawn and start crushing grapes and finish by the end of the day.”

Equipment was modest.

“We had fermenters that came from a farm,” Sleicher says. “They were used on the farm for storage of cow milk or something. Then we had a very crude press. It was just sort of like a barrel with a plunger, and we would just put all the grapes in and turn the press down by hand, squeeze out all juice, and then we would add sulfur dioxide to suppress the wild yeast. Within 24 hours, we would add wine yeast.”

Two years later, the winery released its first commercial wines, a Gewürztraminer and a Riesling.

“The wine was immediately successful,” Sleicher says. “We sold out in one day as I remember.”

All of the wine was sold to local retailer QFC in the University Village in Seattle, a short distance from the University of Washington.

“I remember packing something like 60 cases of wine in my VW bus and hauling that very carefully over to QFC,” Sleicher says.

Effusively positive press from the Seattle Post-Intelligencer helped the wine move at a pace that most wineries today could only dream of. All of the wine was gone from the retail shop within a week.

Working alongside legends

During his time at AV, Sleicher leveraged his background in chemical engineering to assist with winemaking. This continued even after Master of Wine David Lake (1943-2009) joined the team in 1979.

“David Lake and I were the experts on analysis of the wines, what was what was in them and what was good about them,” Sleicher says.

While Associated Vintners started as a group of ten, responsibilities varied. “The whole group depended on three people for judgement, David Lake and me and Lloyd Woodburne,” Sleicher says. “We made all the decisions about how to make the wine.”

Lake had an enormous impact on the Washington wine industry. Most notably, in 1986, he partnered with grower Mike Sauer of Red Willow Vineyard in Yakima Valley to plant the state’s first Syrah vines. Syrah is now Washington’s third most planted red grape variety and makes many of the state’s highest quality wines.

Sleicher remembers Lake fondly, saying, “He was an amazing taster.”

Associated Vintners becomes Columbia Winery

Over time, as the winery grew and needed to raise funds, AV sold Harrison Hill. The winery moved to a new facility in Bellevue. Additional investors were added, and the winery’s name was changed to Columbia Winery in 1983. The founding group unraveled.

“The transition did not go well,” Sleicher recalls. “I think we got pretty much screwed. We lost our shirts on that deal.”

Eventually, Columbia was sold, first to Constellation Brands in 2001 and then in 2008 to Ascentia Wine Estates. California wine giant E. & J. Gallo Winery bought Columbia in 2012. However, the Associated Vintners brand remains with Dan Baty, who had become the majority investor in the winery in the early ‘80s.

Columbia remains active, though the winery recently closed the Woodinville tasting room it had called home since 1988. The legacy of Associated Vintners and Columbia remains far-reaching in the Washington wine industry. From the wines that are made today to the people who worked at Columbia in the early days, the seeds that Associated Vintners planted grew into today’s vibrant Washington wine industry.

A life-long love of Washington wine

After retiring from the UW in 1991, Sleicher became involved in photography, mostly focusing on wildlife. This interest continues to take up his time today.

“Right now, I’m working on getting out a book of my photographs,” Sleicher says. “This will be a coffee table book. I’ve selected 100 photographs. What I have to do now is just the captioning.”

Sleicher, who turns 99 next month, also maintains his interest in wine. The retirement community where he lives has a tasting group. They meet regularly and taste six to seven wines blind and rank the wines.

“Sometimes we agree, and sometimes we don’t,” Sleicher says. He admits that his palate has a strong preference.

“I love Washington wines, and so I don’t drink anything but Washington wines, partly out of loyalty but partly because they’re so good.”

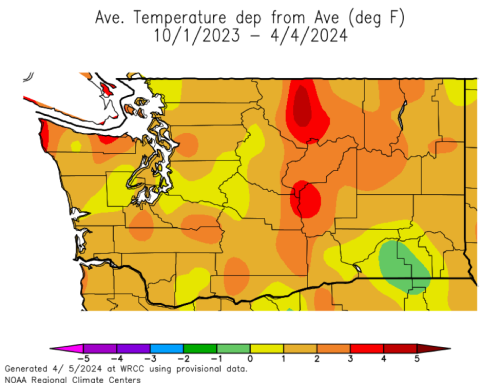

When asked what he thinks makes Washington wines so special, Sleicher’s answer is simple.

“Something called Degree Days. It’s a measure of how much sunshine you get, and we have an ideal amount. The wine growing season is just nearly perfect in Washington. Great place to grow grapes.”

When Sleicher became involved in Associated Vintners, it’s not an exaggeration to say that the Washington wine industry didn’t exist, certainly not for vinifera grapes. Today Washington has nearly 1,100 wineries, 60,000+ acres of wine grapes planted, and is the second largest wine-producing state in the nation. Associated Vintners had a lot to do with that.

“It was a long, joyful experience,” Sleicher says of his time at AV. “I’m pretty proud of my part in it.”

This article has been updated to correct Sleicher’s age as 98 at the time of interview, not 99.

NB: Many of the dates and other historical information used in this article comes from History Link.org’s article “Associated Vintners – Washington’s academic winemakers.” Image courtesy of Charles Sleicher.

NOTE: Northwest Wine Report is now partially subscription-based. Please consider subscribing to support continued content on this site.

To receive articles via email, click here.

Professor Sleicher was one of my favorite professors when I was a chemical engineering doctoral student at the University of Washington in the 60’s – and he nurtured my life long interest in and enjoyment of wine. I fondly remember coming in on a Saturday morning and watching him wash out old wine barrels on the bottom floor of the unit operations lab. I also remember one of his early projects of making wine from Washington apples – trying to match the flavors from an apple wine he remembered from his post doc days in England. His graduate student on this project worked full time supervising Minute Man Missile installations on the west coast and would bring in wine he had purchased while on the road and would share it with his office mates – he had his wife crush all the apples!

Fantastic Article Sean. It took me about 25 years to realize my ChE degree was really a winemaking degree, and a heck of a lot more fun than making plastic or gasoline.