Winemaker Jason Gorski at DeLille Cellars gives a succinct summation of the 2020 growing season in Washington, saying “Yields were down. The quality was great.”

Indeed, at 178,500 tons, 2020 was Washington’s smallest crop since 2012. It was an 11% reduction from 2019 and a full third lower than the state’s highwater mark of 270,000 tons in 2016. While grapes were in shorter supply, winemakers loved what they got.

“Overall, the vintage is spectacular,” says Chris Figgins, president of Figgins Family Wine Estates in Walla Walla Valley. “I’m kind of in love with the vintage right now.”

The stage for the 2020 growing season was partially set in October of 2019. That month, a frost in Columbia Valley was followed by a freeze on October 30th , with the latter appearing to have caused some vine damage.

“We didn’t think too much of it at the time, but I think it made a difference,” says Mike Sauer, who manages Red Willow Vineyard in Yakima Valley.

Unlike 2019 which had an unusually heavy snowpack, winter precipitation was well below average in 2020.

“Everything was dry,” says Dick Boushey, who manages vineyards in Yakima Valley and Red Mountain. “This whole year I watered more than ever.”

For Dan Nickolaus, who manages Champoux, Mach One, Palengat, and Wallula Gap vineyards in the Horse Heaven Hills, this set up what he says was one of his best vintages as a grower. “If you have a dry soil profile and irrigation, you have complete control over those vines right off the bat.”

Bud break began in mid-April, well-aligned with long-term averages but later than a number of recent vintages. Bloom began in late May, consistent with recent years. During bloom some areas experienced a significant wind storm. Others saw rain.

“We were calling in Juneuary,” says Figgins. “Like maybe the first 16 days just well below normal [temperatures], constant drizzles. Terrible set.”

Along with the 2019 freeze, the poor set at bloom contributed to the lighter than expected crop. The final factor was the pandemic, with some wineries deciding not to bring in fruit or to bring in substantially less. This led growers to do heavy pruning and shoot thinning early in the season.

“I kind of said ‘Well, I’m going to grow what I can sell,’” says Boushey.

Of course, throughout the growing season, COVID-19 loomed.

“It was the most challenging year by far,” Boushey says. “So much anxiety, especially at the beginning.”

Growers divided up crews, made sure they were spaced out, and took other precautions to try and minimize risks. Winemakers, who didn’t have the benefit of working outdoors, also had to work through the challenges.

“Everyone was trying to figure out how to operate,” says Gorski. “It was extremely stressful.”

Katie Nelson, previously at Columbia Crest and recently appointed as winemaker at Chateau Ste Michelle, noted that working in the cellar during the pandemic did have its advantages.

“We say cellar work is sort of the original social distancing,” she says wryly.

While June was at times cool and, in some places wet, July weather improved considerably, with warm but seldom hot temperatures. Late July and August saw several heat spikes, with temperatures reaching up into triple digits. As growers and winemakers started to get a better sense of the crop, many were surprised how light it was.

“I think there was a feeling that it was a little bit smaller, but not 25%,” says Kendall Mix, winemaker at Milbrandt Vineyards and Wahluke Wine Company on the Wahluke Slope.

As a result, minimal thinning was done as harvest approached.

“We spent a quarter of what we had budgeted on crop thinning,” says Lacey Lybeck, vineyard manager at Sagemoor Vineyards in the White Bluffs region of Columbia Valley.

Veraison began in late July and harvest in the third week of August, slightly ahead of where it looked to be at the beginning of the season. September temperatures spiked into the 90s, accelerating picking. An unusual Labor Day wind storm brought gusts up to 50-60 miles per hour in some areas.

“I’d never seen it like that before,” says Boushey. “I was like, ‘Geez, what else is going to happen?’”

What else would turn out to be wildfire smoke from California and Oregon.

The smoke came into eastern Washington briefly in early September and then blew out over the Pacific for a week. However, winds eventually shifted, moving it back in through the Columbia Gorge and then Columbia Valley from September 10th to 18th.

“That put a lot of stress on everybody,” Sauer says. “Basically we didn’t see the sun for eight days.”

As has occurred in vintages like 2017 and to a lesser extent in 2018, the smoke impacted maturation in a number of ways.

“The sugar accumulation just flatlined,” said Sauer, “But the nights were just as warm, so respiration was still happening. Berry development was still happening.”

“It was a really good year to be out tasting fruit,” says Mix. “If you weren’t out in the vineyard, you probably missed that.”

With concerns of potential smoke taint, winemakers did small-scale fermentations for sensory analysis. This became even more critical as the intensity of the fires in California and Oregon increased, overwhelming the ability of commercial laboratories to do analytic testing.

“The smoke was just kind of another kick in the pants,” says James Mantone, owner and winemaker at Syncline Winery in the Columbia Gorge.

In the end, however, winemakers were cautiously optimistic that Washington dodged widespread impacts from the smoke. Petit Verdot, Mourvèdre, and Cabernet Franc in some locations appeared to be the most affected.

“I’m still just nervous because it’s my job to be, but I’m very guardedly optimistic as of right now,” says Figgins.

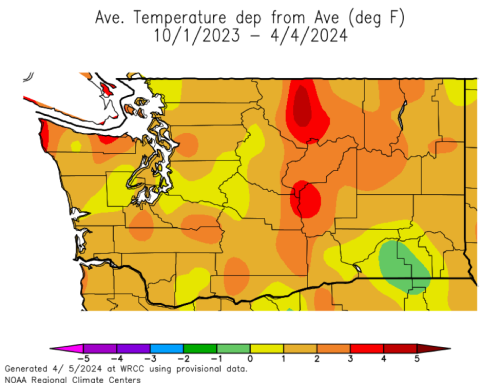

Ideal weather prevailed in the latter part of September, with October seeing above average temperatures. In the end, the big story of the vintage was the small crop.

“It was definitely one of the lighter crops I’ve seen,” says Mary Clubb, owner and managing winemaker at L’Ecole No. 41 in Walla Walla Valley.

Along with factors previously mentioned, other contributors were smaller cluster and berry sizes.

“What we saw was cluster counts were up, but cluster size and berry size were significantly down this year,” says Mantone.

While growers were worried at the beginning of the season about how much they should grow, in the end there was barely enough fruit to go around, with some left wanting more.

“I picked every last cluster,” says Boushey.

Overall, sugar levels were moderate in 2020 as were acidities. While the final Growing Degree Day numbers looked like a very warm season, that was a bit deceiving.

“We were right at or just above the long term average almost during the whole year,” says Clubb. “But then September and certainly for sure October was higher.”

In the end, despite the many stresses of the year, winemakers were extremely pleased with the results.

“They’re just beautiful wines – aromatic and dense but with levity to them and just super dark and good acid. Some of the darkest wines of my career,” says Figgins.

He attributed the dark colors to the summer heat and the poor set giving better sun penetration into the clusters.

“I actually love when we get poor set years,” Figgins says. “They tend to be very high quality years if it’s a solid vintage otherwise.”

A well-forecast frost event October 23rd led many growers who still had fruit out to pick in advance of that or shortly thereafter, bringing the growing season to a close.

While winemakers were no doubt happy with the results of the vintage, many expressed concern about whether consumers would want to drink wines labeled with what was undoubtedly for all a very difficult year. During the growing season, some even questioned whether they should be making wines at all. For Mantone, the answer is an emphatic ‘Yes.’

“People made wine and in the world wars, when the trenches literally went through their vineyards,” Mantone says. “I think [2020 vintage wines] are going to be important wines from a historical perspective and from a psychological perspective. It’s almost more important than ever to be making wine in difficult times.”

skip a vintage?? any year that suffers impending doom is entitled to its vintage … to remember in time, toast nature's resilience, and celebrate those fallen.