“It’s long been known but not named,” Kent Waliser, director of vineyard operations at Sagemoor Vineyards, said recently of the appellation.

Indeed, some of the state’s oldest producing vineyards are in the area. Nearly one in every 10 Washington wineries source fruit from White Bluffs. Additionally, the quality of the resulting wines has proven itself over decades.

Wholly contained within the larger Columbia Valley and spanning 93,738 total acres, White Bluffs has 1,127 acres planted to grape vines. The appellation has nine commercial vineyards and one winery, Claar Cellars. The most planted varieties are Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot, Syrah, Riesling, and Sauvignon Blanc.

Grape vines were first planted in the region starting in 1972 at Bacchus and Dionysus vineyards. These sites are part of Sagemoor Vineyards, which also farms Sagemoor and Gamache in White Bluffs. Together these vineyards comprise the majority of plantings in the appellation. Other vineyards include High River, Mirage, Reed, Wooded Island, and White Bluffs – an estate site for Claar Cellars.

White Bluffs has two main distinguishing features. First, the appellation lies on a plateau approximately 200 feet above the surrounding area. The Columbia River flows south by the appellation’s western boundary, with White Bluffs beginning on the escarpment above the river.

“All the significant acres are on bluffs,” notes Waliser. “The area is kind of like an island.”

The analogy is apt, as this plateau did not rise up from the surrounding area but rather remained after the surrounding land was inundated with water and eroded by the Missoula Floods, a series of cataclysmic, ice age events.

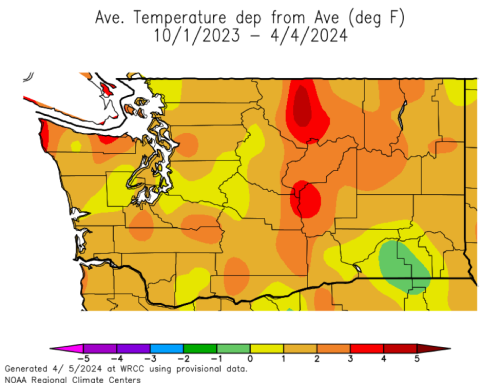

This modest additional elevation, which brings the area from 800 feet above sea level up to about 1,000, allows cool air to drain and helps protect against frosts and freezes. Along with airflow from the Columbia River, this extends the growing season by an average of 45 days relative to lower lying regions. Given that frost and freeze events are the Columbia Valley’s Achilles heel, this gives White Bluffs an advantage.

“Anything that can get you up off the floor of the valley is good,” says Kevin Pogue, a geologist at Whitman College and principal at VinTerra Consulting who was hired to write the appellation application. “Anything that extends your growing season and makes you a little warmer is good.” Waliser says the effects are readily apparent.

The White Bluffs’ second major distinguishing feature is the appellation’s subsoil, which is referred to as Ringold Formation. This is a thick deposit of ancient river and lakebed sediment. On top of the Ringold Formation is a hard layer of caliche (calcium carbonate). Above that are Missoula Flood deposits along with windblown silt and sand.

The thick Ringold Formation and hard caliche layer mean that, unlike almost all other areas of the Columbia Valley, vines planted in White Bluffs will never reach bedrock. “I purposely drew the boundary so that any vine planted in the in the AVA can’t possibly get its roots into basalt bedrock,” Pogue notes.

Vines will therefore interact with a different suite of minerals. Basalt is rich in iron and magnesium. In contrast, Ringold Formation is higher in sodium, potassium, and calcium Pogue says. Additionally, these sediments have a higher clay content. This increases water holding capacity, an important factor in a grapegrowing region where irrigation is vital.

The Ringold Formation runs approximately 30 miles, the length of the appellation. It is exposed in the escarpment above the Columbia River. The white striations in the Ringold Formation, caused by volcanic ash and caliche deposits, give White Bluffs its name.

John Bookwalter, president of J. Bookwalter in Richland, is intimately familiar with the area. His father Jerry moved to Washington in 1975 to manage Sagemoor Vineyards, and John grew up in a home above Bacchus and Dionysus vineyards. These vineyards are the winery’s second largest fruit source.

Bookwalter says the added elevation and proximity to the Columbia River make the area special.

“It’s all about the drainage of the air due to the Columbia River,” Bookwalter says. “It’s not as hot as some areas or as cool as others. There’s power and then the tannin profile still tends to be pretty approachable.”

Mike Januik, owner and winemaker at Januik Winery and winemaker at Novelty Hill, has similarly been using White Bluffs fruit for decades. He says the history of grapegrowing also separates the area.

“They’ve been doing this for a long time,” Januik says. “They’ve got those vineyards figured out.”

Beginning July 19th, wineries can submit labels with White Bluffs on them to the TTB for approval. Given the large number of producers sourcing fruit from the region – a number of whom have already been making vineyard designated bottles for years – Washington wine lovers can expect to see White Bluffs on bottles shortly thereafter.

However, Claar Cellars’ owner Robert Whitelatch, whose family has long advocated for the area to gain appellation status, says the approval is just the beginning of achieving consumer awareness.

“The job’s not over, Whitelatch says. “The job is just starting.”

✝ Candy Mountain, Royal Slope, White Bluffs, and The Burn of Columbia Valley have been approved in the last nine months.

Leave A Comment