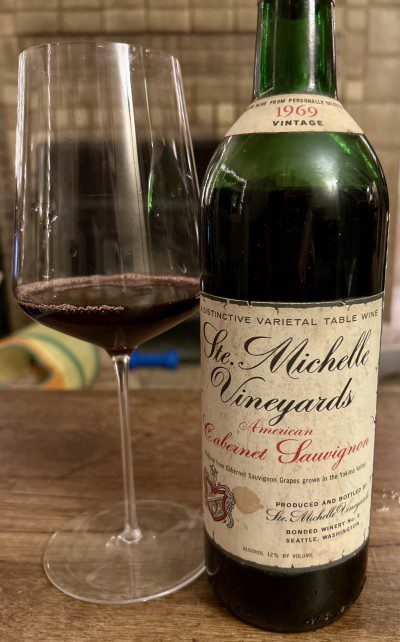

Sometimes it is hard to imagine just how far Washington’s wine industry has come over the last 50+ years. One bottle I recently had – a 1969 Cabernet Sauvignon from Ste. Michelle Vineyards – provides a vinous example of the state’s journey.

Sometimes it is hard to imagine just how far Washington’s wine industry has come over the last 50+ years. One bottle I recently had – a 1969 Cabernet Sauvignon from Ste. Michelle Vineyards – provides a vinous example of the state’s journey.

Chateau Ste. Michelle, considered Washington’s founding winery, has roots that date back to the 1930s. Pomerelle Co., founded in 1934, and National Wine Company, founded in 1935, merged in 1940, rebranding as American Wine Growers (AWG) 15 years later. In 1967, AWG created the Ste. Michelle Vineyards brand, dedicated to making wine from vinifera varieties.

This was a bold move. At the time, the vast majority of Washington wines were fruit or fortified offerings and would remain so into the early ’80s.

AWG was located in Seattle at 9417 East Marginal Way, then and now a heavily industrialized area of the city. The Seattle Times noted the modest building, saying, “Nobody would mistake it for a Burgundian chalet; clearly it is not a Rhine castle.”

In short order, the winery would be rebranded as Ste. Michelle Vintners. Then, in 1976, the winery would move to Woodinville and change the course of Washington wine history, becoming Chateau Ste. Michelle. There are now 130+ wineries and tasting rooms in the town.

Backing up, on August 1, 1969, Ste. Michelle launched its first wines from the 1967 and 1968 vintages. They were a Cabernet Sauvignon, Pinot Noir, Grenache rosé, and Sémillon-Blanc. Those two harvests reportedly yielded a total of 15,000 gallons, approximately 6,300 cases of wine.

Howard Somers (1919-2005) served as enologist and winemaker at Ste. Michelle in the earliest years. Hired by AWG in 1965, Somers was the son of Charles Somers, founder of St. Charles Winery – recognized as Washington’s first post-Prohibition winery. (St. Charles is defunct.) Winemaking took place at AWG’s facility in Grandview, Washington.

André Tchelistcheff, considered to be the most influential post-Prohibition winemaker in America, was hired as a consultant for Ste. Michelle starting in 1967. He would have a profound impact on the state’s industry.

Looking at the 1969 wine I recently opened, this would be Ste. Michelle’s third vintage of Cabernet, made by Somers with Tchelistcheff consulting. It would have been made at AWG’s winery in Grandview. According to Bob Betz, who spent 28 years working for Ste. Michelle and also founded Betz Family Winery, fruit for the early wines came from two vineyards just north of Grandview.

My immediate impression was that the wine was alive – somewhat of a surprise nearly 54 years in. The second was that it was as tart as any Washington wine I have ever had.

My presumption, in addition to the fruit being picked at low Brix (it was listed at 12% alcohol), was that the wine had not undergone malolactic fermentation (MLF). This is a secondary fermentation that softens the overall feel of wine and lowers acidity.

“Harvesting red grapes at 22.5 or 23 Brix from eastern Washington back then delivered grapes with searingly high acidity and correspondingly low pHs,” Betz told me via email. “That makes malolactic fermentation a serious challenge.” Additionally, unlike today, there were not an abundance of commercial yeast available to help primary and secondary fermentation.

Given the difficulties of MLF, Ste. Michelle looked for other means to produce softer wines in the early days. “One strategy was to blend in Merlot with its naturally lower acidity/higher pH and softer mouthfeel,” says Betz. “That was the impetus for the early Merlot plantings.”

Betz notes that the first year Ste. Michelle was able to successfully complete malolactic fermentation on its wines was 1974. Today, malolactic fermentation occurs on virtually all red wines in Washington.

The 1969 wine was listed as “American.” Yakima Valley would not receive its status as a federally approved grape-growing region able to be put on bottles until 1983. Still, the bottle gives a sense of place, noting “Produced from Cabernet Sauvignon Grapes grown in Yakima Valley.”

The 1969 wine was listed as “American.” Yakima Valley would not receive its status as a federally approved grape-growing region able to be put on bottles until 1983. Still, the bottle gives a sense of place, noting “Produced from Cabernet Sauvignon Grapes grown in Yakima Valley.”

For consumers unaccustomed to vinifera wines, the label tries to give context, stating on the back, “This fine wine comes from the superb noble grape from which the famous clarets of Bordeaux and America’s greatest varietal red wines are made.”

When first looking at the bottle, I thought that perhaps the label had considerable wear from its long journey. Then I realized it had intentionally been given a worn look, as if it had come from deep in the cellar, with a neck label saying that it was “Premium wine from personally selected stock.”

The bottle notes Ste. Michelle Vineyards as “Bonded winery No. 8.” Today there are nearly 1,100 wineries in the state. While the earliest vintages of Ste. Michelle yielded 6,300 cases of wine, today the company makes over 7 million cases annually, and Washington as a whole makes over 18 million.

It is notable that one of the wines Ste. Michelle started with was Cabernet Sauvignon. However, in the early decades in Washington, white varieties ruled production.

It would not be until 2012 that red varieties would edge ahead of white wine production and never look back. Cabernet Sauvignon would not become Washington’s most produced variety until 2013. Today, it makes up fully 28% of the state’s production.

The back label reads, in part, “Connoisseurs will enjoy the rewards of laying this wine aside in their cellars for as long as they can wait.” I doubt anyone would have imagined someone waiting over 50 years, but the statement certainly rang true.

Similarly, tasting this wine, it seems unlikely anyone alive then could have foreseen where the Washington wine industry would be today. It is clear, however, from this bottle that they saw the potential.

Sean,

Curious as to how you got your hands on this rare bottle.

Also, who shared it with you?

Hi Andrew, I bought this wine at auction. It was purchased from the winery on release and cellared in a subterranean cellar by a single individual until the time I purchased it.

Great article, Sean.

Thanks for the walk down the road of our wine history here in WA state

Thanks for the kind words Ky!

I loved reading this history, it brought back memories. I suggest that St Michelle’s early history also owes a lot to Dr. Walt Clore, almost as much as the legendary André Tchelistcheff. I remember being in Dr. Clore’s office during June of 1966 (with my dad, an ag consultant who had many sugar beet growing clients, and Clore was then the IAREC expert on sugar beets). On the wall next to me was his map showing Central Washington at the same latitude as Burgundy and Bordeaux. A few years later, St. Michelle began putting a virtually identical map on the back label of their wines. Clore’s map was created to educate and encourage Central WA growers to try vinifera, and of course he is given great credit for his efforts. Interesting timing: U&I Sugar’s decision to close its refineries at Toppenish and Moses Lake in 1970? forced growers to consider new crops, and Dr. Clore would have been well placed to have helped sugar beet growers (like the Hogues, the Mercers, Airport Ranch, and many others) begin experimenting with vinifera. Without growers, no grapes, no St Michelle.

Doug, I absolutely agree regarding Walter Clore. There’s a reason he is officially recognized as the “Father of Washington Wine.” Thanks for sharing the memories!

Hello, Sean.

Thank you, I realty enjoyed reading your great article. I was fortunate to enjoy a few samples of wine and food at Chateau Ste Michelle’s Grandview Winery before it closed down. Thank you for sharing and transporting me (us) through some great history and memories.

Best,

Jeff Curry

I have had a bottle each of the 1967 and 1969 Associated Vintners (Columbia Winery) Cabernet Sav. Both were excellent and alive. Have a bottle of the 1978 Ch. Ste. Michelle Cab that I will open one day soon. Found all of these on Winebid.