The following article was written by Michael Fagin. Fagin is an operational meteorologist providing weather forecasts to clients in the Pacific Northwest and custom forecasts for groups climbing Mt. Everest and other major peaks. Fagin is also a travel writer with a focus on weather and wine.

The following article was written by Michael Fagin. Fagin is an operational meteorologist providing weather forecasts to clients in the Pacific Northwest and custom forecasts for groups climbing Mt. Everest and other major peaks. Fagin is also a travel writer with a focus on weather and wine.

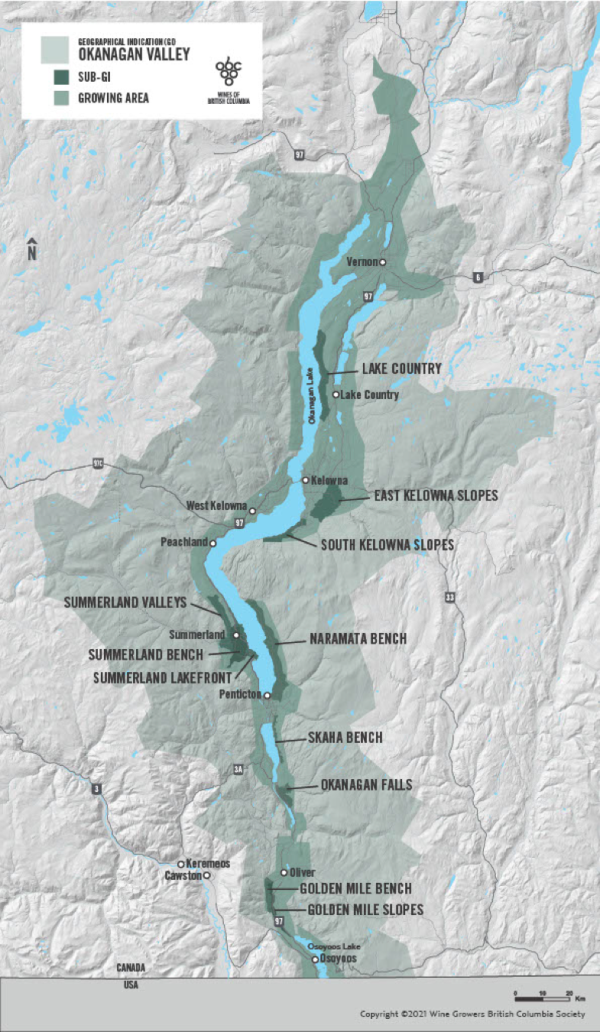

Areas of British Columbia have seen hard freezes from punishingly low temperatures in two successive seasons. The city of Kelowna in the Okanagan saw extreme low temperatures in December of 2022. On December 21st of that year, they recorded a low of –31 degrees Celsius (–24 Fahrenheit). Then on December 22nd, the low was –33 degrees Celsius (–27 Fahrenheit). The high temperature on December 22nd was only –20 C (–4 F).

This approached near record lows. The coldest temperature recorded for Kelowna is –36.1 Celsius (–32.8 Fahrenheit) in 1990.

This event was devastating for the growing region that surrounds Kelowna. It was calculated that wine production in 2023 was reduced by 54% from the freeze.

With El Niño in place for the winter of 2023-2024, many growers were hoping for the forecast above-normal temperatures that normally occur with that event. Unfortunately, on January 13th of this year, Kelowna recorded temperatures of –30 degrees Celsius (–22 Fahrenheit).

Here, we will review what weather conditions brought these recent hard freezes. We will also look at the bigger picture and see if these hard winter freezes are expected to be more common in a climate-changing environment.

Looking back at December 2022

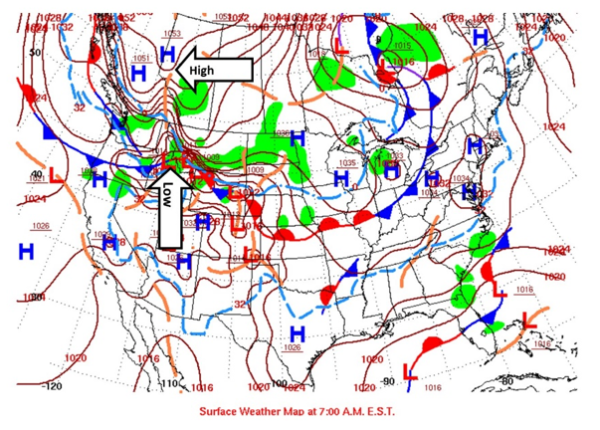

The December 2022 storm was so intense it was given the name Winter Storm Elliott by The Weather Channel. The surface map below depicts December 21, 2022. An area of low pressure is over Eastern Oregon. An area of high pressure is in northern British Columbia.

Surface winds blow in the direction from high pressure to an area of lower pressure. So, in this case, the pressure differential forced the cold air from Northern Canada to the south into British Columbia and Washington (map sources NOAA).

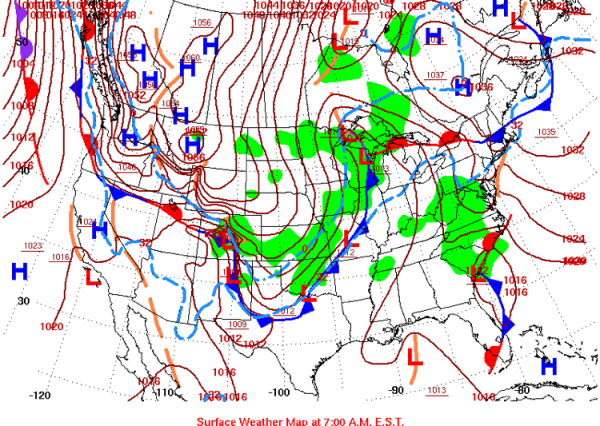

The next day, this same storm quickly moved into the upper Midwest (L on map below). This area of low pressure developed and intensified so quickly that meteorologists call this a Cyclonic Bomb. It resulted in 60 mph winds in Illinois. Essentially every county east of the Rocky Mountains was placed under some sort of winter weather-related advisory.

Looking at January 2024

This January brought weather whiplash to British Columbia. For much of December 2023, many locations had record-high temperatures during parts of the month. Even early January of 2024 ushered in well above-average temperatures.

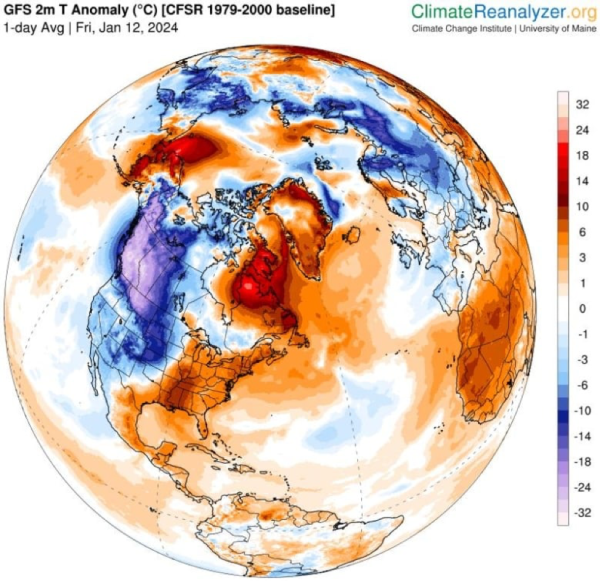

However, temperatures then went from a high of 5 degrees Celsius (41 Fahrenheit) in early January to a high of –20 degrees Celsius (–4 Fahrenheit) by January 12th in Kelowna. Then it hit a low of –30 degrees Celsius on January 13th (–22 Fahrenheit).

Other popular growing regions had record or near record lows. Penticton recorded –28 degrees Celsius (–18 Fahrenheit) and Osoyoos –22 degrees Celsius (–8 Fahrenheit).

The map below shows temperatures for January 12th. Much of British Columbia was close to 22 degrees Celsius below average. Yes, that is 40 degrees Fahrenheit below average!

Growers are just beginning to fully estimate the damage, but it looks to be severe. As a rule of thumb, many European varietals can only tolerate temperatures close to –24 Celsius (–11 Fahrenheit). If these temperatures are reached, then we can expect bud damage. Vines can even die.

Some growers have already indicated that the damage from 2024 is worse than that from December 2022. A question is, why?

One hypothesis is that the damage was more severe given the extremely warm/mild winter that occurred immediately prior to the cold temperatures. Additionally, much of the Okanagan growing area also had only 36% of average precipitation during 2023. Wetter soil moisture tends to retain more heat than dry soil moisture.

Why are these British Columbia hard freeze events occurring?

These hard freeze events are occurring because of the Polar Vortex. This has become a popular phase in the media, especially over the last 10 or so years. However, this term first appeared in meteorological research as early as the 1850s and started to be used more commonly in the 1960s.

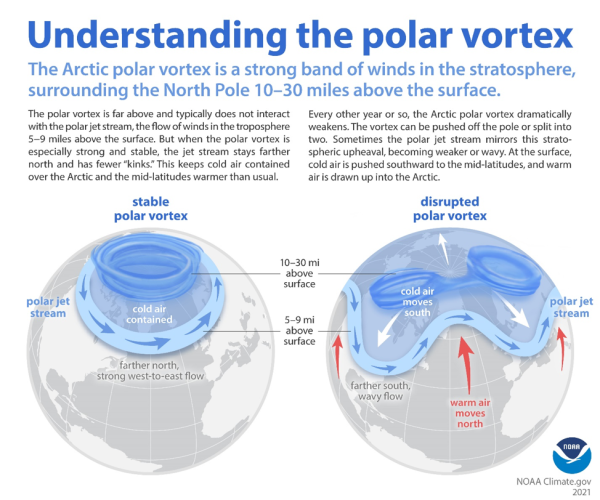

The Polar Vortex occurs in the stratosphere (10 to 30 miles above the earth’s surface). Under normal winter conditions, it is stable and circulates over the North Pole. The associated cold air and the polar jet stream (located close to levels of 30,000 feet) will remain near the North Pole. Under these conditions, North America is usually spared extreme cold.

At times, however, the Polar Vortex becomes disrupted and weaker. This causes colder air to move to the south.

In conjunction with this, the polar jet stream is weaker. As a result, instead of the winds blowing from west to east, the polar jet stream has a wavy flow.

The net consequence is the jet stream winds blow from the north to the south and will drag the cold air towards the south. Eventually, this air can be drawn to North America. Canada and parts of the United States get strong outflow winds from the north. This is usually referred to as ‘modified arctic air.’

It was these types of conditions that led to the cold events in British Columbia in both 2022 and 2024.

Are extreme cold events increasing?

It is a hot topic (no pun intended) whether climate change plays a role in increasing the frequency of these events or not. Several meteorologists have studied if there is currently a greater frequency of the Polar Vortex becoming disrupted. If this happens, then we would have the wavy jet stream and strong north winds drawing the cold air into North America.

One of the main researchers says there is limited data available in the stratosphere to come to conclusions. They state that it could be natural variability with possible climate change components, but it is too early to determine.

Another technical study indicates that, since 1990, there has been a trend of more disrupted Polar Vortex and wavy jet stream events dragging cold air from the north. The authors claim this is related to climate change, which results in the accelerated warming of the Arctic region.

With less Arctic Sea ice there is more moisture available, thus more winter snowfall. This additional snow could be bringing cooler winter temperatures in the north and a greater tendency for high pressure to form in Siberia. With this stronger high-pressure building more often, we would tend to get stronger north winds dragging the cold air toward North America.

The bottom line is, at present, we need more research on this topic to be able to draw conclusions on the relationship between these patterns and climate change.

What might the implications be for British Columbia winters?

The jury is still out if the last two winters of hard freezes will become commonplace with climate change or not. It is possible these were very unusual circumstances of consecutive winters of a hard freeze.

However, if this does become a more common occurrence, the industry will need to look at strategies to try to mitigate the risk. Drastically reducing or, at worst, losing crops is devastating to growers and winemakers alike, especially if it occurs in successive years.

There are a variety of alternatives and protective measures. One solution, though it would be a major change, would be to explore cold hardy hybrids, which are used in cold climate winegrowing regions.

British Columbia is not necessarily there yet. But the recent hard winter freezes and their implications are on the minds of everyone in the growing region.

NB: This article has been updated to correct the historical low in Kelowna as –36.1, not –35.

Northwest Wine Report is wholly subscriber funded. Please subscribe to support continued independent content and reviews on this site. It is the only way that the site will be able to continue.

To receive articles via email, click here.

Not good for our neighbors to the north in the Okanagan Valley, I feel for them, know how much work goes into growing grapes. Initial bud sampling from our vineyards at Hard Row to Hoe on the north shore of Lake Chelan point to similar results. We lost crop as well due to the December deep freeze in 2022.

The report did not distinguish between towards southern BC and the more northern Kelowna-area vineyards. It will be interesting to learn how the Oliver/Oosoyoos vineyards fare.

From what I’ve read (up here in BC), the entire Okanagan and Similkameen crops are wiped out. They think that 1-3% of BC’s crop might produce grapes, but that will primarily be from the Fraser Valley and out on Vancouver Island.

Things are looking really dire for the BC wine crop. The link below called the crop “virtually wiped out.” Estimates are that 99% of the crop is a total loss.

https://vancouversun.com/business/local-business/b-c-wine-crop-facing-catastrophic-losses-after-extreme-january-cold-snap

This is also true for much of the cherry and peach crop out of the Okanagan, as well. Devastating for the agricultural community.