This is the third in a three-part series on Washington wine. Read part I. Read part II.

This is the third in a three-part series on Washington wine. Read part I. Read part II.

There has been a great deal of handwringing and soul searching in the Washington wine industry since Ste. Michelle Wine Estates told growers it was canceling 40% of the company’s fruit contracts this summer. Much of it has focused on what the implications might be for the state and what needs to be done now to get Washington to the next level.

Here, in the third of three articles, I explore areas where the state has, in my opinion, fallen well short. For the purposes of this exercise, as before, I have limited the list to 10 items.

Washington wine: The Ugly

1. In 40 years, Columbia Valley has failed to make a national name for itself.

Four decades ago next year, the Columbia Valley was approved as a federal grape growing region. It is Washington’s catchall appellation, home to 99% of the state’s vineyard plantings. The vast majority of Washington wines bear Columbia Valley on the label.

Unfortunately, during this time, the appellation has failed to gain sufficient consumer recognition. I expect that if wine lovers in the U.S. were asked a) if they have heard of Columbia Valley and b) what state or country the appellation is located, the answers would be dispiriting.

When Columbia Valley was approved, the U.S. appellation system was new and brand awareness was all there for the taking. The state has, to date, failed to capitalize on that opportunity 40 years later.

2. Washington too often tries to define itself by comparison to more prominent wine regions.

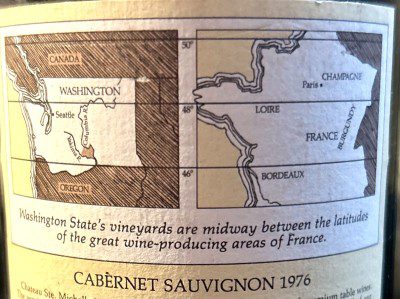

Back label, 1976 Chateau Ste. Michelle Cabernet Sauvignon

Going back to the modern industry’s earliest days, Washington has tried to define itself by comparison to others. Ste. Michelle, starting in the ‘70s, had a back label that showed Washington on the same latitudes as some of the great wine regions of the world. The implication was, in essence, “they make great wine and so do we.”

Washington’s northern latitude is critically important to the wines that the state makes. Being on similar latitudes as renowned wine regions in France is considerably less so.

Even now, contextually, we say that Washington wine has New World ripeness, like California, but structure more akin to some Old World wine regions, such as France. This is true and does help provide context to the wines.

However, in continually comparing the state to others, Washington has failed to singularly create an identity for itself. Washington should unabashedly define itself and its wines by their own attributes, rather than by comparison to the attributes of other, better known regions. Otherwise, how can we truly say we are their equal? This requires a subtle but important change in the language used to talk about the wines.

3. Washington has an embarrassingly low number of women who are head winemakers. People of color are even less represented.

If one looks to California, Oregon, or even Idaho, there are scads of woman winemakers. In Washington, there are not. Why?

As I visit wineries, I am often struck by how many of the people on the winemaking team are women. My hope has been that perhaps, over time, more of these women will be hired as head winemakers or perhaps start their own wineries.

That might still happen. But what we know right now is that Washington has an embarrassingly small number of woman winemakers for an industry of its size. If one extends that out, the number of BIPOC winemakers is orders of magnitude smaller. The state can and must do better in this regard.

4. Washington was late to get started with its sustainability initiative.

Washington launched its sustainability program, Sustainable WA, in 2022. While this was a big moment, the state started on this path considerably later than it should have.

Washington likes to say that it is “sustainable by nature.” Due to the arid environment where the vast majority of the state’s grapes are grown, considerably fewer spray applications are needed than in other areas. This is as true now as it always has been. It’s also a punt on a question that is increasingly important to consumers. The state has needed a way to show that it’s true. (It is.)

Sustainable WA is an attempt to address this. However, at present, it’s just starting. It also only applies to vineyards, not wineries.

Washington’s recent actions on sustainability should be encouraged. However, the state is late to the game and has catching up to do relative to its peers. That said, it’s important to note that there have been other sustainability certifications in which some Washington producers have long participated.

5. There needs to be more cutting-edge viticulture in Washington.

For Washington to advance as a wine region in terms of quality, the majority of the improvements need to take place in the vineyard. This includes what is planted, where it is planted, how it is planted, and how it is farmed.

Several top-end projects in Columbia Valley in the last decade or so have shown the potential. The early results from sites, such as Hors Catégorie and WeatherEye, have been stratospheric.

To be clear, those two specific vineyards are extremely expensive endeavors and are not ones that are easily replicated. Still, they have shown where the bar can be set. For the state to get to the next level, it needs more cutting-edge viticulture to further elevate the wines.

6. Washington needs more wines with a specific sense of place.

Washington makes an abundance of delicious red and white wine. But too many of the wines are just that: delicious. Not enough speak to a specific sense of place.

Part of the reason for this is winemakers select fruit from vineyards across Columbia Valley and then combine them together into a single blend. In this way, the place is a very large region. Part of it is also due to many wines using too much new oak, or perhaps the wrong types of oak, or over-ripened fruit.

Wine is typically at its most exciting when there is a strong sense of place. Washington would be well-served to focus more on this. In fairness, in recent years, there has been a growing number of winemakers doing just this. Of course, some long-timers have been doing it all along.

7. Washington can, at times, have too much group think and be too insular, failing to appreciate the larger wine industry or put its wines in context.

At its best, Washington has excelled with its pioneering spirit and its cooperativity. The state’s growers and winemakers are a mixture of people from within the state and from all around the world, sharing knowledge and rapidly advancing the industry.

At its worst, the industry can be insular and suffer from group think. For example, winemakers can rely on the same vineyards, the same yeast, the same barrels, and the same production methods. They do this not because this has been found over time to be the best way to serve the grapes. Rather, they do it because it’s what others are doing.

Additionally, too often wineries fail to put their wines into the context of west coast wines or world wines more generally in terms of quality, style, and pricing. This can lead to blind spots that hurt the industry in the short and the long-term.

8. Washington has generated a lot of wineries, but too few of them are viable businesses in the medium to long-term.

In the last 20+ years, Washington has grown from around 100 wineries to over 1,000. However, too many of these businesses are passion plays rather than viable businesses. (Note that I say this as someone who has a passion play business that is, generously, questionably viable.)

For the state’s industry to be sustainable in the long-term, it must focus on creating businesses that can either be passed down to generations or that are attractive enough as businesses to be sold.

To be clear, not every winery that starts needs to continue indefinitely. However, right now, too few Washington wineries are positioned to be sold or passed down in the medium-to-long term. This means that not enough of them are truly sustainable businesses, which affects the entire industry.

9. Two of Washington’s most distinctive varieties are currently out of favor with consumers.

In the world of wine, there are always discussions about “signature varieties” – the one variety that defines a region. Personally, I am of the opinion that one variety will never (yes that’s bold, underlined, and italicized) define Washington.

To wit, one would never say “What’s California’s best variety?” “What’s France’s?” Those questions are absurd on the face of them. Washington is no different.

However, there are two varieties that have truly shown themselves to be unique, rivaling if not in some cases exceeding the best examples in the world. Those varieties are, to my palate, Merlot and Syrah. Unfortunately, U.S. consumers are not particularly interested in either at present.

Consumer interests inevitably change. However, it’s a much heavier lift to get people excited about a region they don’t know, offering varieties they aren’t interested in. It’s also tough sledding if, as Washington looks to make its mark, by economic necessity, it needs to avoid or mask two of the varieties at which the state excels.

10. Washington is now trying to get over the hump in the midst of a near perfect storm.

For decades, it’s been clear to many that Washington’s star would one day rise high in the sky. The state is able to produce exceptional quality wines across a range of varieties at competitive prices. Progress has been steady, but gaining greater awareness has also been stubbornly slow.

Now the state is trying to accomplish the same task in the midst of a confluence of extremely challenging factors. The wine industry is contracting. Younger consumers at present seem to have their interests elsewhere. Distributors and retailers are consolidating.

Many large wine companies, who under different circumstances might be well-positioned to turbo-charge the state’s rise, are struggling. Washington’s marketing dollars will also be greatly decreased due to Ste. Michelle Wine Estates reducing its production. Many Washington wineries are now looking inward rather than outward to sell their wines.

Of course, every challenge is also an opportunity for those who see it. Additionally, the fundamentals that make Washington so compelling have not changed. If anything, they’ve grown stronger. Now, however, Washington is sailing into headwinds. The task ahead has become that much harder.

* * *

This is the end of our three part series, focusing on “The Good, The Bad, and The Ugly” of Washington wine. By the nature of the way that I’ve written these articles, it might seem that the “bad” and the “ugly” outweigh the good. They do not.

Each of the items I’ve listed are by no means equally weighted. Washington wine has much more going for it than it has against it.

Rather, I have tried to give an unvarnished perspective of how I see aspects of the industry at present. My criticisms, as always, come from someone with a deep love and profound respect for the industry and the people in it.

It is not my intention to cause harm by sharing these thoughts. Instead, it is my hope that, in offering a critical assessment and saying the quiet part out loud, it might help the industry advance. As the saying goes, the first step in solving a problem is openly acknowledging that one has a problem.

Overall, in talking with people about my assessment of the Washington wine industry in recent months, I say with full honestly that I have never felt more optimistic about the industry than I do right now. I also say that I have never been more concerned.

Perhaps that says something about the state of the Washington wine industry at present. It surely says something about me.

As always, thank you for reading.

NOTE: Northwest Wine Report is now partially subscription-based. Please subscribe to support independent content and reviews on this site. It’s the only way that this site can continue.

To receive articles via email, click here.

Thank you for a very thoughtful assessment of Washington Wine and the industry as a whole. I am in 100% agreement, but especially about Merlot and Syrah, which this state excels at and more people need to take notice of.

Excellent series. Also important, and something that is being constantly worked on, is that the wine has generally always had to move to the consumer. Yakima, the tricities, benton city, etc are largely unappealing for wine consumers to visit and spend time in. These areas are a far cry from Napa, Sonoma or even Paso Robles. Walla Walla has made enormous strides, but even then is quite far away and quickly unexciting, especially during the winter. Woodinville has compensated for this but of course lacks in a key component of a major wine area, grape vines. Getting to McMinnville from Portland or St. Helena from San Francisco are an easy hour drive. Opening a bottle and remembering the place, the sounds and smells and the feeling you felt when you were there are a great part of the wine experience.

Great insights and series Sean. Lots to celebrate, think about and act on. And Bob-O I would differ in your remarks about the Yakima Valley, but have the right to your opinion.

Thank for writing this series. As I have worked in the WA wine industry and agree on majority of your points. However, I believe, like any other industry, people should be judged based on their merit versus gender or race. In my experience, people tend to take advantage of that and not actually have the qualifications to do the job. On the other hand it seems there are still people who won’t hire based on that as well. Hence, gender and race should not be a factor on either side. Thanks for the your input. I really enjoyed reading it.

People don’t buy products; they buy meaning. Without a clear definition of its meaning, the full potential of Washington wines will never be reached. What to do? Start with an iron-clad commitment from key stakeholders to compete differently.

again I agree with your big picture. am wondering how many east coast winos know any appellation beyond napa and maybe sonoma, and can tell you what an estate wine is? so I do not agree that those areas are low hanging fruit for us to go after. I do think this does fall even more on our wine commission with ste michelle backing off. do they have the financing/leadership to address this?

I like your point about the East Coast especially considering states like NY, MA, NJ are large import markets. Consumers want quality, price, and a story and don’t fixate on estate sourcing – it is irrelevant, at least when we’re talking about the most immediate need of trying to increase volume and awareness of WA wines on a national scale.

I disagree with your point about the Wine Commission. WA needs to totally redefine itself as a region and take some risks in order for there to be substantial/scalable wines for anyone to promote. SMWE has been looking to competitors and copying their successes, but has been consistently late to the game and has come up short. What if SMWE took a moment to consider what WA can do well and what its winemakers and growers are most proud of? Ignore Nielsen, IRi, and other consumer data for five minutes and let passion and quality drive the ship (infectious). Risky, yes, but if successful, the results could redefine WA. What’s riskier? Continuing down the current path as we’re all aware of those results to date.

Great series. So much potential for Washington wine but many challenges as well. I think that lack of a signature grape variety is something of a challenge from a storytelling perspective. The remoteness of the growing regions is also a challenge. I would also add as an area of opportunity that so many of our Seattle area farm to table restaurants tend to feature European wines to pair with their dishes crafted from locally sourced ingredients. The other side of the coin is that Washington wineries (especially large ones) could do a better job of crafting more food friendly wines. This situation has improved of late but still has a long way to go. We recently had a lovely meal at Crafted in Yakima which did a great job of pairing local ingredients with Washington wines. Thanks for such an in depth and thoughtful series!

Great series, Sean. I’ve enjoyed your “passion business” for years and find I’m in agreement with all most all your observations. I too believe Columbia Valley is such a cornucopia of vineyards, clones, micro-climates that it’s AVA designation means little to consumers. Sort of like “If you can’t say anything about your wine, say it’s from the Columbia Valley.” I’ve had some product from Weathereye and they were fantastic and priced accordingly.