“I’m afraid that all this time we’ve been growing grapes in a low desert.”

One of the biggest misunderstanding about Washington as a grape growing region comes from the western half of the state’s strong branding. When people think of the Washington, they think of evergreen trees and soggy Seattle. How could Washington grow wine grapes in such a climate?

In fact, almost all of Washington’s grapes are grown east of the Cascade Mountains where it is a desert, receiving a mere 6 to 8 inches of rainfall per year. (Seattle by comparison receives an average of about 40.) But there is another significant misunderstanding about Washington wine country, and it is one for which writers are largely responsible.

Most writers correctly emphasize the critical point that Washington’s grapes are grown in the desert. Why is this so important? First, Columbia Valley, Washington’s largest appellation, is consistently warm during the summertime, like most deserts. This allows wine grapes to fully ripen.

Second, because the grapevines are planted in such a dry environment, growers need to use irrigation to ensure that the vines get sufficient water. This allows Washington to create consistently top-quality wines because growers have a high amount of control over the vines’ water status.

But here is where some writers take liberties. They note that Washington grows most of its grapes in the desert, but for reasons unknown, they transform it into a high desert.

Perhaps it’s because they are being influenced by Hollywood, where high deserts are always in vogue. There are paeans like High Desert and Horror in the High Desert. Perhaps it’s because high deserts sound more dramatic, with visions of cowboys and shootouts. Nobody ever boasted about it being high noon in the low desert. Low deserts get no love.

However, we’re here to change that. The Columbia Valley, my friends, is a low desert.

Generally speaking, most sources define high deserts as lying between 2,000 and 4,000 feet above sea level (for example, see California and Oregon). Almost all of Columbia Valley’s plantings lie between 600 and 1,500 feet above sea level. In fact, the Columbia Valley’s upper boundary is set at 2,000 feet in elevation in some areas – exactly where a high desert might begin!

However, Columbia Valley being a low desert isn’t just semantically important. It’s a critical part of why the state is able to grow wine grapes.

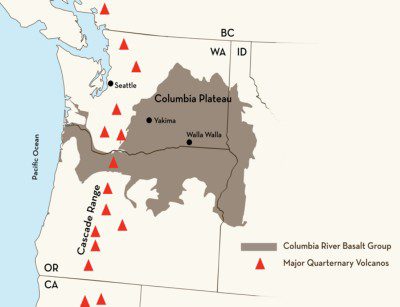

Much of the Columbia Valley is defined by gigantic basalt flows that took place millions of years ago and covered much of modern-day eastern Washington, north-eastern Oregon, and western Idaho. In some areas, the basalt is as much as 16,000 feet thick! To give a sense of scale, that would be over 1,500 feet taller than Washington’s Mount Rainier!

Much of the Columbia Valley is defined by gigantic basalt flows that took place millions of years ago and covered much of modern-day eastern Washington, north-eastern Oregon, and western Idaho. In some areas, the basalt is as much as 16,000 feet thick! To give a sense of scale, that would be over 1,500 feet taller than Washington’s Mount Rainier!

The basalt in the Columbia Valley is so thick that it actually weighs down the earth and causes it to depress. This is the reason that the basalt in some areas of the Columbia Valley is actually below sea level despite being more than 150 miles inland.

What do you get when you’re a) in a desert in summer and b) at very low elevations? It’s very hot!

It’s actually because Columbia Valley is a low desert that the area is able to grow wine grapes. There is sufficient heat for grapes to ripen.

Why is Red Mountain, one of Washington’s most prized appellations, so darn hot? Because it’s a low desert. It’s true of all of the Columbia Valley’s other sub-appellations as well.

One only needs to look to north-eastern Oregon, where elevations quickly get up above 2,000 feet to see what a difference this increase in elevation makes. There are, generally speaking, not a lot of wine grapes grown there. (NB: Some growers have recently planted above 2,000 outside the boundaries of the current Walla Walla Valley appellation.) Ripening grapes at that elevation would be a challenge.

So next time you’re extolling the virtues of the Columbia Valley, by all means emphasize that the grapes are grown in a desert. It’s critically important. But if anything, note that it’s a low desert. If it were a high desert, Washington likely wouldn’t be growing wine grapes in Columbia Valley at all.

Graphic courtesy of the Washington State Wine Commission.

Note: This article has been updated to clarify that it is the basalt that is below sea level, not the current topsoil.

NOTE: Northwest Wine Report is now partially subscription-based. Please consider subscribing to support continued independent content and reviews on this site.

To receive articles via email, click here.

I’m curious, where exactly are the locations where Columbia Valley is below sea level?

Heather Harding, a geologist mentioned this to me once. I’ll inquire about the location.

The basalt is below sea level in some places. However flood deposits have filled in hundreds of feet in some areas. McNary Dam is at 344 feet elevation. Everything in the basin is above that or under water, even the river bed is 200+. Everything below 1100 feet is affected by the Ice Age Floods.

High Desert isn’t clearly defined. Some say above 2,000 feet, some say 4,000.

Any definition puts 90%+ of the Columbia Basin in plain old desert. Desert is generally accepted to be less than 10” annual precipitation. Some of the edge areas in Walla Walla, Spokane, etc.

receive over 10”.

On my farm in the last 20 years we have been between 5.6 and 8.3. We can see what is often the highest US precipitation, Mt. Rainer, more properly named Tahoma.

Good stuff Paul, as always. Thank you!

Most of what Paul says is spot on. There are a few places where the Missoula floods eroded the Columbia river bed below sea level in the Columbia River gorge, but there is no place in the Columbia Basin where the surface of the land or water is below sea level. The surface of the basalt is below sea level in the Pasco basin, but is overlain there by Pliocene lake beds and fluvial gravels (Ringold formation) and glacial outburst flood deposits, which brings the basin floor up to 300+ ft.

Thanks for the added detail Kevin!